Why do males of so many vertebrate species have shorter lifespans than females?

Males and females show differences in lifespan and aging within nearly every animal group for which life history has been studied. The reasons behind this “longevity gender gap” persist as major questions for evolutionary biology and demography alike. I am working on parallel longitudinal-studies in matched wild and lab populations of brown anole lizards (Anolis sagrei) to identify sex differences in longevity and aging while testing for sex differences in the fitness benefits (i.e. offspring left behind) of a long lifespan.

Females brown anoles live shorter lives than males even among the subset of animals that survive to reproductive maturity.

Males show a decline in body condition with age that is not apparent for females.

How and why are males and females of the same species so different?

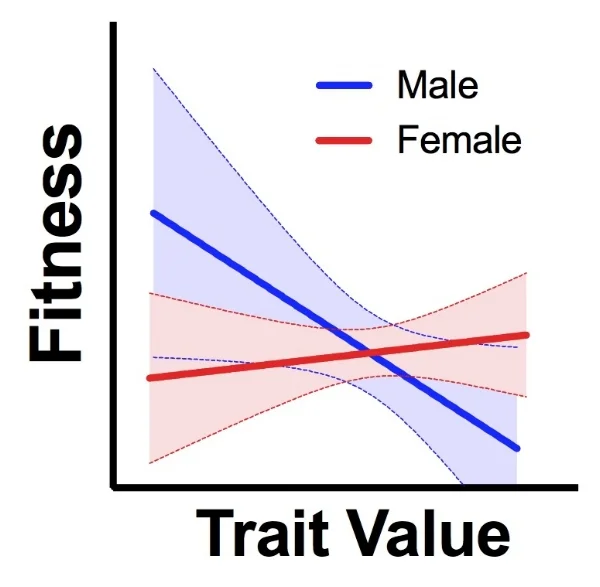

Males and females of the same species share most of the same genes. However, despite their shared genome, the traits and underlying genes that make a successful male are frequently not the same as those that make a successful female. This sets up a genomic and evolutionary tug-of-war between the sexes known as intralocus sexual conflict as natural and sexual selection pull males and females in different evolutionary directions. My current research is focused on this sexual conflict and ultimately on the larger questions it poses in evolutionary biology.

My ongoing work uses wild populations of brown anole lizards (Anolis sagrei) because of their extreme sex differences. I use islands as living laboratories to study evolutionary processes in the wild.

The relationship between a trait and fitness is often very different for males and females. Natural selection can pull the genome in different directions for each sex.

Intralocus sexual conflict

I am using mark-recapture methods and genetic assignment of parentage with GT-Seq to track the survival and reproductive success of more than 6,000 individual lizards across 4 generations in an island population of brown anole lizards. This will allow for a large scale test of many of the fundamental predictions of intralocus sexual conflict theory. Do families with high fitness males have low fitness daughters?

Individuals of both sexes showed an acute increase in stress hormones while engaged in mating behavior (amplexus).

Comparing stress hormones in both sexes

Hormones play key roles in mediating the tradeoff between survival and reproduction. Stress hormones can inhibit reproduction and improve chances of survival during periods of stress. However, stress hormones can also be associated with successfully engaging in energetically costly reproductive behaviors. Our work found an acute increase in the stress hormone, Cortocosterone, during courtship for both male and female red spotted newts.

Males and females similarly had more body fat and fewer parasites after reproduction was surgically eliminated.

Costs of reproduction in both sexes

Costs or reproduction are rarely studied in both sexes at the same time. Sexual selection theory proposes that males suffer increased parasitism as a cost of expressing sexual signals. Life-history theory proposes that females suffer costs because of inherent trade-offs between reproduction and self-maintenance. Surgical elimination of reproduction in both sexes showed that both sexes pay similar costs of reproduction in terms of energy storage and parasitism.

Texas high school students showed the presence of chemical cues from a predatory fish altered the wing sizes of male and female A. aegypti mosquitos and altered the degree of sexual dimorphism in the experimental population.

Classroom science

I work with teachers and kids to push the limits for classroom science. The work of my students done in a Chicago Public School showed how female anoles choose nest sites and how those choices influence fitness traits.

I am currently co-advising Evolution Education teacher fellows Brandon Pope and Nick Kiriazis. Pope and his students are testing the effects of predators on the development of sexual dimorphism in mosquitos. Kiriazis and his students are examining repeatable individual differences in the behavior of cockroaches.

Collaborators at Florida field site: Robert Cox. Ariel Kahrl. Brandon Pope. Nick Kiriazis. Albert Chung. Cara Giordano. Cheyene Sams.